- Publications >

- Report

Profiting Off Lifelines - Nebraska County Jail Phone Systems Lead to High Costs and Unfair Trials

Document Date: November 30, 2017

Introduction

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual freedoms and liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. We serve thousands of members and supporters stretching across the great state of Nebraska.

Criminal justice policies in Nebraska and across the United States have created a system of mass incarceration which hurts our communities and disproportionately impacts low-income families and communities of color. Imprisonment is a brutal and costly response to crime that traumatizes incarcerated people and hurts families and communities. It should be the last option, not the first. Yet the U.S. incarcerates more people, in both absolute numbers and per capita, than any other nation in the world. For the last four decades, this country has relentlessly expanded the size of our criminal justice system, needlessly throwing away too many lives and wasting trillions of taxpayer dollars.

Nebraska has a role to play in reducing America’s addiction to incarceration and providing programs that help those accused or convicted of a crime to turn their lives around.

Acknowledgments

Grateful appreciation to Senator John McCollister for introducing LR 208 and Senator Patty Pansing Brooks for introducing LR 198 to study the question of how high phone rates are impacting children of incarcerated parents.

Research and data collection by Nathan Calvin, Grinnell College, Class of 2018.

Executive Summary

Today, 5.1 million children have a parent behind bars. In Nebraska, that’s 41,000 young people or about one in ten children who have a parent who has been or is currently incarcerated.[1] For these kids, losing a parent to incarceration can be as traumatic as losing a parent to death or divorce.[2] For families with a loved one in jail or prison, phone contact is often the only way to connect on a routine basis. Over half of the Nebraskans in county jail are not yet convicted of any crime—they simply lack the money to post bond and go home as they await their trial.[3] They aren’t there briefly—a nonviolent offender who cannot post bond spends an average of 48 days in jail.[4]

“EMMA” | A Nebraska Story

Emma’s son was away at college when he was approached by another student asking to buy a gram of marijuana—in other words, enough to roll between one and three joints. Her son wasn’t normally a dealer, but he had pot and agreed to sell it. The other student then revealed himself to be an undercover police informant. Emma’s son had no prior criminal history, but because he was charged with a felony, he was given a high bond the family can’t afford.

As of the writing of this report, Emma’s son has been in the county jail for five weeks.

Emma lives 60 miles from the jail and visits twice a week. For the other days, she must rely on the phones to communicate with her son. So far, Emma has already spent over $300 on phone calls. “I constantly put money on his books, but I definitely speak less to him just because I can’t afford to call as much as I want. This $20 drug transaction is costing the county a lot of money to house him in jail and is costing me hundreds of dollars to stay in touch to be supportive. He’s never been in trouble before and he’s having serious depression so it’s important that I stay in touch. I don’t understand how this is benefiting anyone.”

Incarceration already falls disproportionately on the poor and on communities of color. While only one in ten Nebraskans is a person of color, five of ten pretrial detainees in Nebraska county jails are people of color.[5] The burden also disproportionately affects parents of young children. Federal studies show that 60% of women in prison are mothers of a child under 18.[6]

The ACLU of Nebraska has received repeated complaints from families struggling financially to stay in touch with an incarcerated family member. We have also received multiple reports from attorneys who aren’t able to have a confidential phone call with their clients in jail. Over the summer of 2017, ACLU of Nebraska used open records requests to learn more about the cost of calls from behind bars. Our findings unveiled a statewide problem of county jails charging exorbitant rates arising from kickback agreements in which county officials grant private for-profit companies monopoly contracts in exchange for a cut of the profits. In contrast, the state Department of Correctional Services has banned all phone commissions and set a clear standard for county jails to follow.

If you’re not incarcerated, a call home to your family might cost a few cents a minute or just be bundled into your monthly package. But people detained in county jail are charged up to $19 for a 15-minute phone call. Because county jail detainees rarely or never have the chance to earn money behind bars, the financial burden of these unconscionably high rates falls entirely on their families.

For-profit prison phone companies charge sky-high rates to incarcerated people and their families, making it too expensive for families to stay connected. The financial burden often falls on families of incarcerated people because prisoners cannot afford the outrageous charges. Poor people are grossly over-represented in the exploding prison population—national studies show that between 60 to 90% of prisoners are indigent and qualify for a public defender because they are poor.[7] When a parent is incarcerated, that almost always means a major loss of household income, which exacerbates the family’s financial circumstances. If the family doesn’t have gas money for in-person visits or inflated phone rates, their financial hardship prevents prisoners and their families from communicating at all.

Phone companies should not be able to profit off incarcerated people trying to be good parents or good family members. Steep prices mean many prisoners will not be able to call home as often as they would choose. This is no way to achieve our shared goal of public safety. At least 95% of people currently in prison will return to our communities after they complete their sentences.[8] The average Nebraska prisoner will serve two to six years before being released home.[9]

When people keep in touch with their families while in prison, studies repeatedly show they are less likely to commit new criminal offenses after returning to the community and less likely to wind up back behind bars. Keeping family ties strong not only prevents recidivism—it also strengthens the mental health and well-being of the children left at home.

We should adopt policies that help them succeed after their sentences—not encourage them to fail. When people keep in touch with their families while in prison, studies repeatedly show they are less likely to commit new criminal offenses after returning to the community and less likely to wind up back behind bars.[10] Keeping family ties strong not only prevents recidivism—it also strengthens the mental health and well-being of the children left at home. We know there are many children impacted by parents in jail–approximately seven in ten women under correctional sanction have minor children at home.[11] By ensuring family contact, officials can secure taxpayer savings, public safety gains and better outcomes for the families.

Who profits from this present destructive system of jail phone service? The phone companies and, sometimes, the county jail. In this market, specialized phone companies compete for the right to exclusive contracts in each jail. In exchange, the county gets a “commission” by the phone company, and it encourages jail officials to inflate calling rates rather than keep them affordable. One FCC commissioner called this system “the clearest, most egregious case of market failure” she had seen in sixteen years as a regulator.[12]

“Every day, an inmate makes a call, a family member receives a call, and someone profits from the call made...[we’re] paying the highest verifiable commissions available.” – Screenshot and quote from an actual Encartele advertisement.

The for-profit corporations aren’t hiding the financial gain involved: they actually advertise the kickback system. In the promotional sales video created by Nebraska-based company Encartele, the voiceover says “Every day, an inmate makes a call, a family member receives a call, and someone profits from the call made...[we’re] paying the highest verifiable commissions available.”[13] The video depicts a grandmother picking up the phone while a cartoon sheriff is shown shaking a money tree raining dollar bills.

While the companies win, everyone else loses. Prisoners and their families suffer financial hardship or fall out of touch. As a result, the community as a whole is likely to suffer when the jails return them to society more alienated and less connected to positive influences.

Telephone access in jail is also important for ensuring people facing criminal charges get their fair day in court. If you’re locked in a jail cell facing serious charges, a telephone call to your lawyer may be your only hope to clear your name and get back to your job and family. But, given the high rates for phone calls described above, even calling a lawyer while in county jail can be very difficult.

Our survey revealed that a few counties are following best practices by providing appropriate free and confidential calls to a lawyer. However, other counties impose the same crushingly expensive rates for even a call to the attorney appointed to an indigent person. We’ve received reports of people unable to leave messages for their lawyer because they were collect calls, calls that dropped in the middle of a conversation if the call lasted longer than the amount the prisoner had on their card, and jails providing no private space for making a confidential attorney call.

“The ‘Profiting Off Lifelines’ report adds to mounting evidence showing that children pay a hidden and significant cost when it comes to our adult justice system. All children need meaningful contact with their parents, especially during stressful circumstances, and policies that permit financial exploitation of parent-child relationships are contrary to Nebraska values.”

Julia Tse, Policy Coordinator, Voices for Children in Nebraska

National Landscape

Spurred by a grandmother’s complaint to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and after a lengthy study of egregiously high phone call costs for people behind bars, the FCC issued regulations in 2013 and 2015 to cap the cost of prison and jail phone calls.[14] The FCC set different rates for county jails (which house pretrial detainees not yet convicted of any crime as well as people convicted with a short sentence) and for state prisons (which house people convicted with a longer sentence). By July 2017, the proposed FCC caps on collect calls within a state (intrastate) were to be:

- 36 cents per minute for county jails that housed between 0-349 people

- 33 cents per minute for county jails that housed between 350-999 people

- 32 cents per minute for county jails with over 1,000 people

- 13 cents per minute for all state prisons.

For collect calls between more than one state (interstate), there was a hard cap of 25 cents per minute regardless of facility size. The FCC also placed caps on the surcharges and transaction fees telecommunications companies could impose.

Before the rate caps could go into effect, for-profit telecommunication companies challenged these intrastate regulations in court, arguing they violated the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. The federal court agreed, leaving the interstate regulations standing but striking down intrastate rate caps.[15] This ruling was about the limits of the FCC’s authority, not the wisdom of the regulations and in no way an endorsement of the status quo, as the court noted these charges “raise serious concerns” and called some of the rates charged by jails and prisons “extraordinarily high.”

The FCC rate cap of 25 cents per minute on prisoner phone calls made from one state to another still stands, but most prisoners are serving time in their home state, which is not covered by the FCC rate cap order. In order to stop the abuse, it will take action by the state legislature to emulate the FCC and end this predatory practice for all county jail phone calls.

The end of the FCC intrastate rate caps has passed the regulatory baton to the states. Now, state by state, we must take action to tailor remedies against these abusive practices.

Phone Rates for Prisons in Nebraska

State prisons

Nebraska state facilities have already stepped up to this challenge. The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services (NDCS) has a regulation forbidding commissions “in the interest of making inmate calling as affordable as possible.”[16] As a result of this decision, Nebraska state prisons boast one of the lowest call prices in the nation, at 5 to 10 cents per minute depending on whether it is a local call or not. This means a prisoner can call home anywhere in Nebraska to connect with their family for 15 minutes and it will only cost $1.50. Even an indigent prisoner without any funds has a monthly option to choose either five free stamps or a free $2.50 calling card.[17]

One human rights organization has ranked Nebraska state facilities as the best phone rate in the country.[18] Additional research has shown the prices in Nebraska are not as low as indicated in that ranking, but Nebraska rates are clearly among the lowest nationwide. See Appendix for state phone rates. Our state prison system ban on kickbacks or commissions should be a model for all county facilities.

County jails

In contrast, Nebraska county jails are permitted to receive unlimited commissions from phone companies, have no limits on the rates for intrastate calls, and have no caps on surcharges. This is particularly troubling since county jails are shorter-term facilities than prisons, and approximately one half of the county jail population are pretrial detainees who are actively defending cases in which they are presumed innocent but are unable to post bail to go home. As last year’s ACLU of Nebraska report on debtors’ prisons revealed, the average person charged with a non-violent offense will spend 48 days in jail before his or her case is decided.[19]

Pretrial detainees have a heightened need to contact their attorneys to prepare their case but, as discussed later in this report, many jails impose the same costs for a call to a lawyer as they do for a call home. In the summer of 2017, the ACLU of Nebraska sent out open records requests to all 64 county jails in the state asking for the rates they charged prisoners and detainees.[20] A copy of our open records request letter is in the Appendix.

In comparison to the $1.50 a state prisoner will pay for a 15 minute call, we discovered county detainees may expect to pay between $2 and $20 for that same 15 minute call, depending on the county in which they’re housed.

The results of our survey were startling. In comparison to the $1.50 a state prisoner will pay for a 15 minute call, we discovered county detainees may expect to pay between $2 and $20 for that same 15 minute call, depending on the county in which they’re housed.

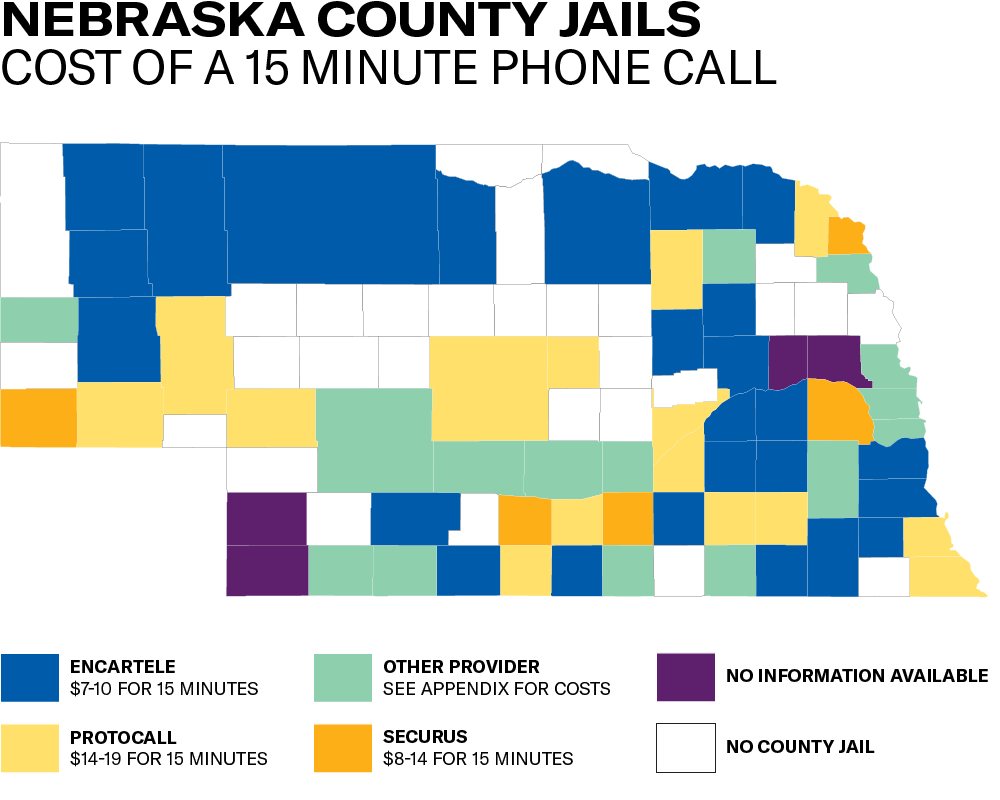

Nebraska counties are using several for-profit companies based throughout the country. The three largest providers in the state are:

- Encartele, based in Nebraska (26 counties): average cost $7-10 for 15 minutes

- Protocall, based in Kansas (15 counties): average cost $14-19 for 15 minutes

- Securus, based in Texas (5 counties): average cost $8-14 for 15 minutes

These initial rates that prisoners and pretrial detainees are charged do not include additional ancillary fees that many of these companies also impose. In the FCC rate cap lawsuit the court found that 38% of the for-profit prison phone call company revenue is generated by ancillary fees.[21] Some of the extra charges we identified in Nebraska include:

- $2 a month just to open and maintain an account (Protocall)

- $2 a month to receive a paper bill (Global Tel*Link)

- $3 for each call through any wireless phone (Protocall)

- $3 to pay by credit card (Global Tel*Link)

- $8 to add funds to your prepaid account (Securus)

A county-by-county breakdown of the cost of calls can be found in the Appendix. Most of these for-profit companies have a long history of being sued for poor quality service or exorbitant fees.[22]

| County | County Income from Jail Calls |

County Budget 2014-2016 |

Population Rank 2016 Estimate② |

Monthly Cost to Prisoner Making four 15 minute calls a week |

% of Weekly Income for a family of four receiving SNAP benefits③ |

Gallons of Gas for the same cost as monthly phone calls④ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas

|

$617,062

|

$320,756,053

|

1

|

$41.76

|

2%

|

17

|

| Lancaster

|

$397,566

|

$140,932,017

|

2

|

$50.40

|

3%

|

22

|

| Scotts Bluff

|

$77,265

|

$29,432,616

|

7

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

| Sarpy

|

$38,464

|

$90,238,404

|

3

|

$41.76

|

2%

|

17

|

| Lincoln

|

$37,470

|

$20,798,297

|

8

|

$99.68

|

4%

|

40

|

| Platte

|

$33,898

|

$23,891,430

|

10

|

$99.68

|

4%

|

40

|

| Dawson

|

$30,152

|

$23,399,633

|

13

|

$96.48

|

4%

|

39

|

| Saunders

|

$28,028

|

$36,217,734

|

15

|

$168.16

|

6%

|

68

|

| Saline

|

$22,139

|

$10,880,133

|

20

|

$318.24

|

12%

|

129

|

| Buffalo

|

$20,461

|

$26,348,262

|

5

|

$160.96

|

6%

|

65

|

① www.nebraska.gov/auditor/reports/index.cgi?county=1

② Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division

③ http://dhhs.ne.gov/children_family_services/Pages/fia_guidelines.aspx

④ https://www.bls.gov/regions/mid-atlantic/data/averageretailfoodandenergyprices_usandmidwest_table.htm#ro3xg01apmw.f.1

The amount of income that jails make from the calls compared to the actual costs of the calls varied widely from county to county. Some counties received income of a couple hundred dollars last year. Other counties reaped astonishing amounts of money from the families of poor people totaling $1,407,327.25 across the state (counties with highest revenue from jail phones seen in Table A). For example, Lancaster County reaped $397,566 in 2016 and Douglas County took in $617,062 in 2016. Incarceration should never be a profit generator for the government—especially when half of those behind bars in county custody are pretrial detainees who are presumed innocent as they seek to defend themselves against a pending case. But this jail call money-making scheme is a modern twist on the Victorian for-profit debtors’ prisons.

| County/Counties | County Income from Jail Phones |

|---|---|

| Adams, Dakota, Kimball, Phelps and Saunders Counties | Prepaid Calls: $2.99 per month Transaction fee: $7.95 Collect Calls: $3.49 per month |

| Antelope, Cheyenne, Custer, Dixon, Fillmore, Garden, Hamilton, Harlan, Kearney, Keith, Merrick, Nemaha, Richardson, Saline, Valley, and Washington Counties | Monthly Fee: $2.00 Per call fee for phones (including wireless) without a billing arrangement: $3.00 |

| Douglas County | Automated Payment to Card: $3.00 Paying by Live Operator $5.95 Paper Bill $2.00 |

| Lincoln County | Deposit: $3.00 |

| Average | Highest | |

|---|---|---|

| LOCAL | ||

| Collect | $8.10 | $14.85 |

| Pre-paid Debit | $5.70 | $8.75 |

| Pre-paid Collect | $7.66 | $14.85 |

| INTRALATA | ||

| Collect | $9.23 | $14.85 |

| Pre-paid Debit | $6.34 | $11.50 |

| Pre-paid Collect | $8.44 | $14.85 |

| INTERLATA | ||

| Collect | $9.54 | $15.10 |

| Pre-paid Debit | $6.66 | $14.30 |

| Pre-paid Collect | $8.47 | $14.85 |

| INTERSTATE | ||

| Collect | $3.98 | $16.41 |

| Pre-paid Debit | $3.35 | $7.50 |

| Pre-paid Collect | $3.75 | $7.50 |

“Cristie” | A Nebraska Story

Cristie’s fiancé was held as a pretrial detainee on federal drug charges in a county jail for almost a year. In-state rates were costing her about $6 per 15 minutes, even though calling from an out of state number would have cost $4 per 15 minutes. “It’s not fair—they know your family is likely to be closer by, so they charge more to call down the street than it costs to call across the continent.” Her fiancé was experiencing intense anxiety and depression at the outset and was relying on her to help locate witnesses his attorney could then contact. “I ended up paying over $800 to stay in touch with him. The kids and I had only my income, and there were months when I had to tell him he wouldn’t hear from us until my next payday. It especially impacted my 14-year-old who knew she would have been in touch if only we’d had more money.”

Emerging Issues Needing Further Study

There are three areas our investigation revealed will need further study.

State Prisoners in County Facilities

State prisoners in state facilities have commission-free telephone services. However, it appears that state prisoners who have been transferred to county jails due to overcrowding are paying the same exorbitant phone rates as the county detainees. According to the most recent NDCS data, there are 94 state prisoners housed in county jails.[23] Since state prison sentences can be many years long, these prisoners and their families may have to pay these much higher rates for years.

Video Calling

Video calling services have emerged as an option in some Nebraska county jails, including Lancaster County.[24] These systems, which the companies describe as “video visitation,” are advertised as being similar to Skype or Facetime video calls, although the actual calls are reportedly lower quality and less reliable.[25] Instead of treating video calls as a supplement for in-person visitation and phone calls, some jurisdictions have experimented with prohibiting all in-person visits, leaving families with only telephone contact or video calls—both of which are, not coincidentally, typically provided by the same telephone provider. The rates and surcharges for video calls are completely unregulated, and like telephone calls, similar commission-based profit incentives are often involved. Studies have concluded that the video call rates are very high nationwide.[26] Recent news reports suggest a similar high cost in Nebraska[27], but further study is necessary to identify all the rates, surcharges and fees associated with video calling systems.

Accommodations for Prisoners who are Deaf

Prisoners who are deaf most commonly use a videophone to make calls: the video screen allows the person to sign to their loved one or to an interpreter who relays the prisoner’s words to the family member. Nationwide, many correctional facilities still only have outdated TTY systems where an operator reads the typed words of the person who is deaf. It is a slow and cumbersome process that does not promote effective communication.[28] We did not investigate the best modern technology or policies needed to ensure that a county jail detainee who is deaf may have meaningful and reliable contact with an attorney or a family member. This impacts a significant number of Nebraskans—according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, approximately 6% of prisoners have a hearing disability.[29] Failure to provide appropriate accommodations may trigger a lawsuit like those that have been filed successfully in Idaho, Virginia, Florida, Maryland and Kentucky.[30]

“Farrah” | A Nebraska Story

Farrah is a refugee and naturalized US citizen. Her adult nephew was arrested for a nonviolent misdemeanor earlier this summer, and because he is not yet a citizen, he worries he might be facing deportation in addition to a criminal conviction. Farrah and her nephew’s mother live in Lincoln, but the young man is housed in a rural jail in central Nebraska that is a 90-minute drive each way. Since it’s difficult to travel that far, the family relies primarily on phone calls. Farrah reports her nephew is having a very hard time in jail: the facility is overcrowded, there is no open-air exercise, and many guards and prisoners are hostile to him because he is a minority. He is desperately worried about what will happen with his criminal charge as well as his immigration case, so his family tries to talk to him as much as possible to buoy up his spirits. “We pay about $6 per call, plus $10 every month to cover all the other fees. He tells us he hasn’t seen the sun for weeks, and we are his only ray of hope when we are able to afford that call.”

Attorney Calls in Nebraska

County jail detainees don’t just need to talk to their families—they also need to call their lawyers. The vast majority of county jail detainees are represented by public defenders due to their indigent status. In greater Nebraska, public defenders and court appointed lawyers may be required to cover territory across several counties. Their far-flung clients may be many hours apart from each other and the attorney’s office, so telephone calls are less burdensome than traveling for personal interviews. Each prisoner needs to be able to communicate with his or her attorney to prepare for trial and confer about their case. That’s a tall order when the cost of the call is very high or when the client can’t even leave a voicemail or speak without the fear that the sheriff might be listening in.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to counsel for people charged with criminal offenses. It includes the right to have a competent defense that has not been compromised by government eavesdropping or rendered unaffordable by the greed of jail officials.[31] Confidential discussions between an attorney and client are the bedrock to a meaningful defense and are privileged communications.[32] Courts have been particularly protective of a pretrial detainee’s right to adequate and confidential phone calls with their attorney because these rights are essential to receiving a fair trial, and a pretrial detainee is presumed innocent. The Eighth Circuit, which is the federal circuit court of appeals covering Nebraska, has ruled “Pre-trial detainees have a substantial due process interests in effective communication with their counsel . . . when this interest is inadequately respected during pre-trial confinement, the ultimate fairness of their eventual trial can be compromised.”[33]

Given this body of caselaw, jails risk expensive civil rights litigation if they fail to provide adequate confidential phone calls with attorneys that are free for all indigent people. Otherwise, when a pretrial detainee is trying to decide whether to spend her few dollars on a call home to talk to her children or call her lawyer to prepare for trial, we’ve set an impossible choice before her.

Our survey revealed significant variance in internal rules in place to protect the attorney-client relationship. Thirty-one counties have no written policies governing attorney-client call confidentiality. Only twenty seven counties provide free calls to attorneys. Eight other counties permitted free local attorney calls or free calls to public defenders while charging for all other attorney calls. See Appendix for a complete breakdown of policies and costs for attorney-client calls.

Confidentiality

The ACLU survey on attorney-client calls was prompted in part by reports from lawyers who have had their conversations with incarcerated clients recorded without their knowledge. Such recordings infringe on the attorney-client privilege, which is a foundational principle of our legal system and is essential to providing a competent defense.

In one example, the court appointed an attorney to represent a defendant facing serious felony charges, but the attorney’s office was an hour and a half away from the Hall County jail where his client was housed. Given the distance, the attorney had to rely on phone calls to prepare for the upcoming trial. In the routine discovery process, prosecutors provided the attorney with a CD containing all his client’s phone calls from the jail. When the attorney reviewed the CD, he was shocked to find he was listening to his own calls with his client: in fact, the sheriff had recorded 59 phone calls between the attorney and client and provided those recordings to prosecutors. The attorney successfully moved to seal the phone calls and disqualify all current prosecuting attorneys in order to prevent the prosecution from gaining an unfair advantage from the confidential attorney conversations.[34] However, the whole episode raises troubling questions about what other attorney-client calls in Hall County or other jails might be improperly recorded and shared with prosecutors.

“My clients at [undisclosed] county jail have one phone to use: a pay phone on the wall in a common area without any privacy. I need to ask them questions about their upcoming case but sometimes they’re scared to answer me because other prisoners or county jail staff are standing nearby.”

Another attorney told us, “My clients at [undisclosed] county jail have one phone to use: a pay phone on the wall in a common area without any privacy. I need to ask them questions about their upcoming case but sometimes they’re scared to answer me because other prisoners or county jail staff are standing nearby.”

While jails may have legitimate reasons to record prisoner conversations in some circumstances, such as when a prisoner is attempting to use the phone system to threaten witnesses or coordinate illegal activities, the jails must have safeguards in place to ensure attorney conversations are not caught in a recording dragnet.

Most jails reported they have no written policy on the issue. A few reported anecdotally that while they have no written policy, and despite the fact they confirmed they record all calls, they promise they do not listen to a recording once they realize it is between an attorney and their client. However, this is no substitute for actually installing a system designed to safeguard the attorney-client privilege—especially since these phone companies specialize in prison and jail phone systems. Securus, the phone provider in five Nebraska county jails, is currently being sued in a class action in California for continuing to willfully record attorney-client phone calls despite repeated warnings of the problem.[35] They’ve also been caught recording calls in Missouri in what has been called the “most massive breach of the attorney-client privilege in modern U.S. history.”[36]

In some counties, the telephone system offers the option to put attorneys’ phone numbers on a “do not record” list. However, several county officials admitted their list of attorneys was far from comprehensive and that it was likely some attorneys were falling through the cracks and being recorded. Only a few counties were following best practices in that they have a phone that is physically separate and offers a consistent non-recorded line for attorney calls.

As the Nebraska Supreme Court Lawyer’s Advisory Committee on ethics has said, “A defendant held in a government detention facility, like any other client, is entitled to expect that his communications with his lawyer will be confidential” and “mere assurances from the government” are not adequate to safeguard confidentiality.[37] Lawyers representing Nebraskans in county jails deserve clear statewide standards to ensure there is no eavesdropping by government officials.

“I expect the prosecutors to do everything they can to try their case and win. I also expect prosecutors to play fair and follow the rules. I’ve been shocked to learn how often the basic principles of attorney-client privilege aren’t being followed. When a jail passes along information from a confidential phone call I have with my client to the prosecutor, I can’t effectively represent my client. Cutting corners isn’t how our judicial system should work,”

Ben Murray

Germer Murray & Johnson

Attorney call cost

Our survey revealed that the cost of attorney calls varies widely across the state. Some counties confirmed that they always charged attorney calls at the same rate as a call home. Other counties had exceptions and allowed free calls to public defenders while still charging for calls to any private attorney. The majority of counties had no written policies about the cost of calls to legal counsel.

One attorney who is appointed to represent indigent clients in a large five-county area told us “I regularly have difficulty getting calls from my clients. Even though I was court-appointed precisely because the client has been found to be poor, the county jail says, ‘Your client needs to pay for it on his own or he can call you collect.’ That just shifts these ridiculously expensive calls to me and I’m not being reimbursed by the court. Yet I can’t conduct my business by driving over an hour every time I need to communicate an update or pose a question to my client.”

Another attorney shared, “my client started in one county jail that offers free calls to attorneys, but when he was moved to a county without free lines, I contacted the Sheriff to request phone access. I was told ‘this isn’t our problem and we won’t do it. You’ll need to work it out somehow.’ I could drive the hour and a half to see him, but ironically I’ll end up billing that time to the county so there is no savings to deny this man his attorney calls.”

Recommendations

There are several reasonable ways to reform phone access for prisoners in county jail. Nebraska county jails have the excellent model policies from the state NDCS that could be adopted county-by-county. State policymakers should pass legislation to ensure consistent access to family and legal counsel.

SOLUTION: Public Service Commission regulations

The Nebraska Public Service Commission (PSC) could study the issue and, like the original FCC regulation, issue a regulatory rate cap and restrictions on ancillary fees that would apply to all county facilities. The PSC would first need statutory authority to regulate in this arena.[38] New Mexico has already enacted such a jail telecommunications rate regulation through their state public service commission.[39]

SOLUTION: Nebraska Jail Standards Board regulations

The Nebraska Jail Standards Board could be charged with the task of setting a regulatory rate cap and restrictions on ancillary fees for all county jail facilities. The board would also be best positioned to draft model policies regarding protecting the confidentiality of attorney client calls.

SOLUTION: County Board action to ban commissions

County boards could prohibit commissions from phone contracts, following the model of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services. The Nebraska Association of County Officials could provide model policies to ensure appropriate rates and fees that reflect the actual cost of providing telephone service.

SOLUTION: State statute ban on commissions and rate cap

The Legislature could pass a state law that resembles the “no commissions” rule used by the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services. Legislative reform of the for-profit telecommunications industry is already gaining momentum on a national scale. Illinois[40], Michigan[41], Mississippi[42], New York[43], New Jersey[44], New Mexico[45] and several other states have passed laws that capped rates and ended the practice of taking commissions in their state prisons. Legislation is pending in Montana[46] to make all attorney phone calls free. The best model is from New Jersey, where a 2016 bipartisan bill affecting both state prisons and county jails banned commissions, surcharges and fees, and capped in-state call rates at 11 cents per minute.[47]

A state law rate cap could follow the original FCC model with different rates depending on the size of the jail to account for the lower profitability in smaller rural counties.

SOLUTION: Further legislative study of impact on prisoners who are deaf, state prisoners in county care, and the cost of video calling systems

Our investigation was limited in scope regarding the questions about true phone access for prisoners with disabilities (especially those who are deaf); how state prisoners housed in county facilities due to overcrowding are charged; or how the emerging trend of video calling systems is impacting indigent families. A legislative resolution to study these issues further may help illuminate areas ripe for additional reform.

Conclusion

Expensive phone rates and policies in county jails aren’t just affecting the men and women behind bars—these practices also impact families and children. Cutting off lifelines to children, to families and to lawyers not only endangers the wellbeing of the incarcerated person but also harms their family members and threatens public safety by increasing the risk of recidivism.

Additionally, recording attorney phone calls and making it impossible for indigent people to call their public defenders undermines the legitimacy of the criminal justice system.

Jail phone service is a classic case of market failure, in which regulators must step in to ensure fair pricing and adequate functionality. In this broken “market,” specialized phone companies use monetary commissions to entice government officials to sign monopoly contracts. Meanwhile, the people who actually use these telephone systems—incarcerated people, their families and attorneys—are shut out of the contract negotiations and must suffer the inflated phone rates and limited functionality that result from a market that prioritizes commission revenue over price and quality of service. Common sense reforms to guarantee confidential attorney contact and limit the cost of calls to the actual cost of the service are needed to ensure a better result for those behind bars, their families and our communities.

[1] Annie E. Casey Foundation, “A Shared Sentence: The Devastating Toll of Parental Incarceration.” Voices for Children in Nebraska. 2016. http://voicesforchildren.com/a-shared-sentence-the-devastating-toll-of-parental-incarceration/

[2] LaVigne, Nancy et al. 2008. “Broken Bonds: Understanding and Addressing the Needs of Children of Incarcerated Parents.” The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/broken-bonds-understanding-and-addressing-needs-children-incarcerated-parents

[3] ACLU of Nebraska, “Unequal Justice: Bail and Modern Day Debtors’ Prisons in Nebraska,” December 2016, page 13. https://www.aclunebraska.org/app/uploads/drupal/sites/default/files/field_documents/unequal_justice_2016_12_13.pdf

[4] Id., page 17.

[5] Id., page 21.

[6] U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report, “Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children,” (2010). https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmc.pdf

[7] Marea Beeman, Am. Bar Ass’n, Using Data To Sustain And Improve Public Defense Programs 2 (2012). http://texaswcl.tamu.edu/reports/2012_JMI_Using_Data_in_Public_Defense.pdf

See also Bureau Justice Assistance, Dep’t Justice, Contracting For Indigent Defense Services 3, n.1 (2000), available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/181160.pdf and Caroline Wolf Harlow, Bureau Justice Statistics, Dep’t Justice, Defense Counsel In Criminal Cases 1 (2000), available at http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/dccc.pdf (over 80% of people charged with a felony in state courts are represented by public defenders).

[8] Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Reentry Trends in the U.S.,” 2017. https://www.bjs.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm

[9] Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Annual Report (2014), p. 47

[10] See, e.g., Travis, McBride, and Solomon. 2006. “Families Left Behind: The Hidden Costs of Incarceration and Reentry.” The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/families-left-behind Also Duwe, Grant 2011. “Blessed Be the Social Tie That Binds: The Effects of Prison Visitation on Offender Recidivism.” Criminal Justice Policy Review. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0887403411429724 Also Bales, William 2008. “Inmate Social Ties and the Transition to Society: Does Visitation Reduce Recidivism?” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022427808317574

[11] Susan W. McCampbell, “The Gender-Responsive Strategies Project: Jail Applications” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2005. https://nicic.gov/gender-responsive-strategies-project-jail-applications Approximately 51% of male prisoners are parents of a minor child. Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children,” 2008. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmc.pdf

[12] Statement of Commissioner Mignon Clyburn on Rates for Interstate Inmate Calling Services, WC Docket No. 12-375. http://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2014/db1017/DOC-330005A3.pdf

[14] FCC, “Inmate Telephone Service.” https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/inmate-telephone-service

[15] Global Tel*Link vs. FCC, 866 F.3d 397 (D.C., 2017). https://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/C62A026B396DD4C78525813E004F3BC5/$file/15-1461-1679364.pdf

[16] Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Administrative Regulation, “Inmate Telephone Regulations,” No. 205-03, XII, “Commissions.” https://www.corrections.nebraska.gov/system/files/rules_reg_files/ar_205.03_2017_final.pdf

[17] Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Administrative Regulation, “Inmate Telephone Regulations,” No. 205-03, IIID. https://www.corrections.nebraska.gov/system/files/rules_reg_files/ar_205.03_2017_final.pdf

[18] Prison Phone Justice. https://www.prisonphonejustice.org/

[19] ACLU of Nebraska, 2016. “Unequal Justice.” https://www.aclunebraska.org/en/publications/unequal-justice

[20] Although there are 93 counties in Nebraska, not every county has a jail.

[21] Drew Kukorowski, Peter Wagner & Leah Sakala, Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates, and Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry, p. 3 (2013). https://static.prisonpolicy.org/phones/please_deposit.pdf

[22] Markowitz, Eric, International Business Times. “Video chats are replacing in person jail visits, while one tech company profits.” April 8, 2015. http://www.ibtimes.com/video-chats-are-replacing-person-jail-visits-while-one-tech-company-profits-1873918

[23] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, July-September 2017.https://www.corrections.nebraska.gov/sites/default/files/files/39/datasheet_2017_3rd_qtr.pdf

[24] Lancaster County Department of Corrections Visitor Information. http://www.lancaster.ne.gov/correct/visitors.htm#Contact

[25] Prison Policy Initiative “Video Calling,” https://www.prisonpolicy.org/visitation/

[26] Lapowsky, Issie, Wired Magazine. “Video chat price-gouging costs inmates more than money.” August 31, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/prison-video-visits/

[27] Hicks, Nancy. Lincoln Journal Star, “You will now be able to video call your jail inmate, for a price.” September 27, 2017. http://journalstar.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/article_49e1196a-c68d-59f2-a0c5-4dffd7d6b6fa.html

[28] Thompson, Christie, The Marshall Project. “Why many deaf prisoners can’t call home,” September 19, 2017. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2017/09/19/why-many-deaf-prisoners-can-t-call-home

[29] U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. “Disabilities Among Prison and Jail Inmates,” December 2015. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/dpji1112.pdf

[30] Marshall Project, Id. Cases are also still pending in Michigan, Illinois and Massachusetts.

[31] See, e.g., Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 828 (1977) (prisoners have a constitutional right to access the courts) and Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343, 355 (1996) (prisoners are entitled to court access)

[32] See, e.g., Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 403 (1976) and Weatherford v. Bursey, 429 U.S. 545 (1977)

[33] Johnson-El v. Schoemehl, 878 F.2d 1043, 1051 (8th Cir. 1989)

[34] State v. Foster, Order, Case. No. CR14-10 (Nuckolls County District Court).

[35] Friedmann, Alex, Prison Legal News. “Securus Faces Lawsuit Over Recorded Attorney Calls.” August 2, 2016. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2016/aug/2/securus-faces-lawsuit-over-recorded-attorney-calls/

[36] Smith, Joran, The Intercept. “Not So Securus: Lawyers Speak Out About Massive Hack of Prisoners’ Phone Records.” February 12, 2016. https://theintercept.com/2016/02/12/not-so-securus-lawyers-speak-out-about-massive-hack-of-prisoners-phone-records/

[37] Nebraska Ethics Advisory Opinion for Lawyers No. 13-04. https://supremecourt.nebraska.gov/sites/default/files/ethics-opinions/Lawyer/13-04_0.pdf

[38] See Neb. Rev. Stat. 86-139 regarding the PSC scope of authority.

[39] NM Title 17, Chapter 11, Part 28. http://164.64.110.239/nmac/parts/title17/17.011.0028.htm

[40] 730 ILCS 5/3-4-1 (2016) http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/documents/073000050K3-4-1.htm

[41] HB-4323 (2017), Sec. 219 page 50 https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2017-2018/billengrossed/House/pdf/2017-HEBH-4323.pdf

[42] House Bill No. 265 http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/documents/2016/pdf/HB/0200-0299/HB0265IN.pdf

[43] N.Y. COR § 623 http://codes.findlaw.com/ny/correction-law/cor-sect-623.html

[44] N.J. Rev. Stat. § 30: 4-8.11 – 8.14 (2016) http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/PL16/37_.PDF

[45] NM Title 17, Chapter 11, Part 28. http://164.64.110.239/nmac/parts/title17/17.011.0028.htm

[46] 2017 Bill Text MT D. 1071 (H.B. 258) http://leg.mt.gov/bills/2017/billpdf/HB0258.pdf

[47] N.J. Rev. Stat. 30:4-8.11 – 8.14 (2016) http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/PL16/37_.PDF

Related Issues

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.