It sounds cliché, I know. But after nearly a decade of working with youth who have experienced major trauma, I am convinced that The Beatles had it right. We are born to be social creatures, and, like food and water, we need the love and connection formed within human relationships to survive. To serve as my daily reminder of just how important love is, I had a small heart tattooed on my wrist a couple years ago.

Research has continuously and increasingly highlighted the impact of trauma on human development. Trauma that occurs during childhood, in particular, has been shown to have significant and long-lasting impacts on the brain, which ultimately affects behavior. I am sure many of us have seen children and youth being disrespectful towards authority figures, acting disengaged in the classroom, and quickly escalating from anger to violence.

What we’re really seeing here is the result of sustained trauma.

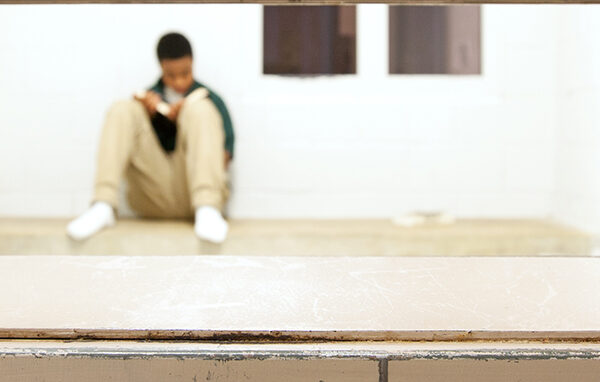

Instead of focusing on the source of the behavior — oftentimes traumatic experiences — the common response in the United States is to throw young people in locked facilities and refuse them the one thing that truly has the capacity to make a change: human relationships. This is currently standard practice in the state of Nebraska, as the ACLU of Nebraska has documented in “Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska.” The report shows that kids in juvenile justice facilities are being held with minimal human contact and limited access to exercise or fresh air for up to 90 days straight.

Solitary confinement is a dangerous, damaging, and counterproductive practice. As a social worker, I call it torture. We cannot just lock a young person away in a room by themselves and hope the problem naturally resolves itself. We have to try a little harder than that. Thankfully, some lawmakers in Nebraska are already working on reforms, starting with better monitoring and reporting. Nebraska’s largest media outlets have joined the call for reform.

If we hope to help young people learn from their mistakes and heal from the wounds of their past, we have to acknowledge the rocky childhoods and community violence and institutional oppression so many of these youth have experienced at home, on the streets, and in juvenile detention. We have to stop viewing them as criminals and start seeing them as young people full of potential, worthy of investment, and deserving of love. And we have to help them view themselves in this light as well.

My favorite example of this is Jacob. When I met Jacob four years ago, he was torn between two worlds: the negative influences of his past and the type of life he wanted for his future. Over the years, I have watched Jacob try his best to leave behind the childhood full of abuse, gang affiliations, and isolation.

But Jacob is not alone. I have watched the world continuously knock him down, as our systems often do to young Black men.

As a teen, Jacob spent a significant amount of time in solitary confinement. He received no therapeutic benefit from the practice. But with the unconditional love, support, and reassurance myself and a couple other adults have provided, Jacob is now rising. He has become a community advocate and volunteer, trying to prevent other youth from falling into the same patterns he was susceptible to. Jacob is a perfect illustration of how the power of human relationships can help overcome the damage of previous trauma compounded by solitary confinement.

Every time I’m asked about the small tattoo on my wrist, I reply with the infamous Beatles’ song title. I explain the ultimate lesson I’ve learned from my time spent with young people over the years. I tell them that it’s my reminder to look beyond the hurt and strive to respond with love.

I hope someday we’ll be able to view our approach to criminal justice in the same manner. Currently, with the use of solitary confinement, we’re casting those most in need of love aside and traumatizing them again instead.

We can and must do better for our young people, our society, and ourselves. Please join me in calling for reform to juvenile solitary.