Unequal Justice

Providing equal justice for poor and rich, weak and powerful alike is an age-old problem. People have never ceased to hope and strive to move closer to that goal. — Griffin v. Illinois, 351 US 12, 16 (1956)

Table of Contents

Executive Summary | Criminalization of the Poor | Bail Reform | Modern-Day Debtors' Prisons |Conclusion | Table of Offenses | Methodology | Bond Schedules

Executive Summary

Over 30 years ago in Bearden v. Georgia, the United States Supreme Court issued a seminal ruling that to imprison someone because of their poverty and inability to pay a fine or restitution would be fundamentally unfair and violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Yet today, courts across the United States and Nebraska routinely imprison people because of their inability to pay. This practice has been termed a “modern-day debtors’ prison.” This practice happens at various points in the criminal justice system. First, it can happen to people who are awaiting trial. Individuals are forced to sit in jail while their case proceeds because a bail amount has been set beyond their ability to pay while those with financial resources regain their freedom to go to work, school and be with their families while awaiting trial. Second, some people who have been adjudicated and found guilty end up in jail even though they were not sentenced to jail time because they are unable to pay a fine and are imprisoned instead to “sit it out.”

The end result of these systems: a maze with dead-ends at every turn for low-income people.

In this report, the ACLU of Nebraska presents the results of its investigation into Nebraska’s modern-day “debtors’ prisons” and bail practices. The report shows how, day after day, low-income Nebraskans are imprisoned because they lack the ability to pay bail or pay fines and fees. These practices are illegal, create hardships for those who already struggle, and are not a wise use of public resources. Debtors’ prisons result in an often fruitless effort to extract payments from people who may be experiencing homelessness, are unemployed, or lack the ability to pay.

The ACLU of Nebraska investigated the imposition of bail as well as the imposition of court fees and fines. Our survey focused on the four largest counties (Douglas, Lancaster, Sarpy and Hall), using open records requests, court record review, interviews with people involved in the system with additional in-court observations in Douglas, Lancaster and Sarpy Counties.

Key Findings

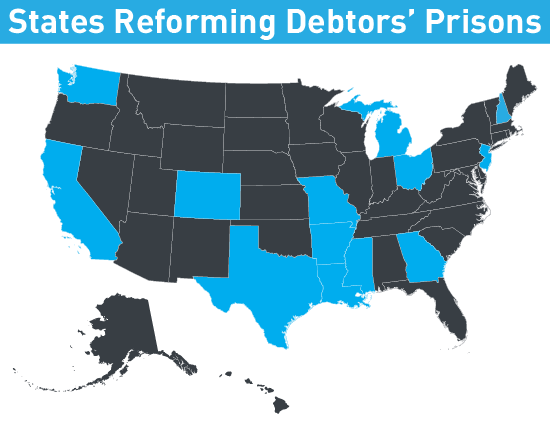

Nebraska doesn’t have as many problematic practices as found in other jurisdictions. Some states have notorious abusive practices such as private bondsmen who use dangerous tactics to apprehend low-level offenders, staggeringly high interest rates and late fees that make it nearly impossible to ever pay off court costs, and additional fees for serving jail time or applying for a public defender. Therefore we believe Nebraska is well positioned to reform our system to remedy the harms currently being inflicted on people who are poor.

Human Costs

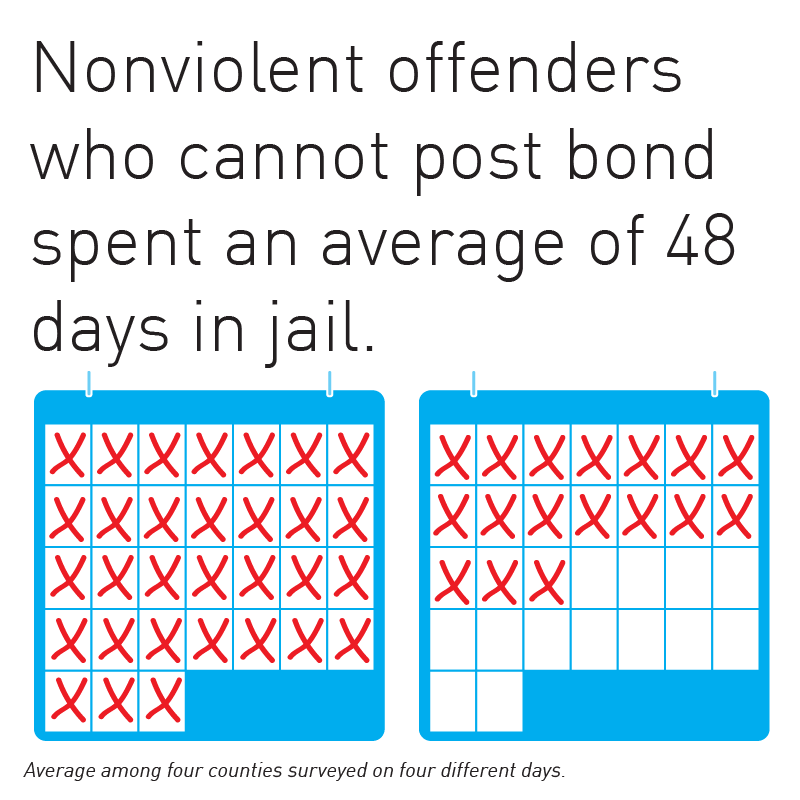

Being held in jail comes with devastating human costs for low-income Nebraskans. Being held in jail while awaiting trial means one is more likely to be found guilty and more likely to receive a stiffer sentence. People who are in jail—whether pretrial or whether sitting out a fine—face significant disruption to their lives. Before they even get to trial, Nebraska defendants charged with nonviolent offenses spend an average of 48 days behind bars. Being imprisoned has a destabilizing impact on their jobs, their children, and their wellbeing. These burdens fall on people who were already struggling and at risk. It is well documented that racial disparities exist at every stage of our criminal justice system. This research shows a clear and disturbing overrepresentation of people of color behind bars in Nebraska as well.

Waste of Taxpayer Money and Resources

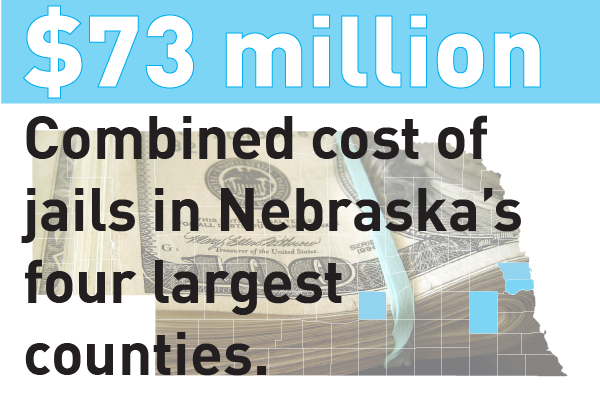

Incarcerating low-income people prior to trial or requiring an indigent defendant to sit out a fine costs much more than counties actually recoup. Our study revealed that over half of the county jail populations were pretrial people—Nebraskans presumed innocent but unable to afford bail to go home. At the same time, several counties are facing overcrowded jails and are burdened by paying other counties to take their inmates. Indigent defendants sitting out a fine are doing so at taxpayer expense—it costs between $80-90 per day per inmate, depending on the county involved. The annual costs to run the jails in our four largest counties will reach over $73 million in 2017. Both practices strain county budgets and burden taxpayers unnecessarily.

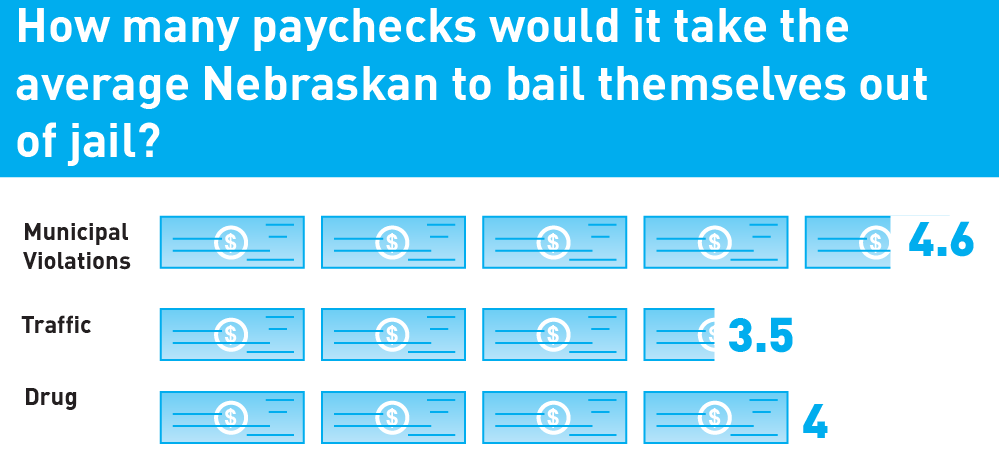

Jailing the Poor Creates a Two-Tiered System of Justice

Bail should be limited to people who pose a true risk to public safety or who present a concrete flight risk. All other defendants should be allowed to go home on their own recognizance. Instead of an individualized assessment of dangerousness and flight risk, Nebraska is reflexively placing a cash bail amount for most defendants. This means the wealthy go home while the poor remain behind bars, though studies show there is no rational basis to treat the poor more harshly. Similarly, when a wealthy defendant is sentenced to pay a fine, they can do so and go on their way while a poor defendant without the means to write a check must sit in jail. Nebraska deducts $90 per day served from court fines, so even a nonviolent misdemeanor offense can result in many days in jail. These practices mean the poorest defendants are punished more harshly than those with money.

Recommendations

The ACLU of Nebraska has made recommendations to judges, police and policymakers to remedy the serious abuses that have resulted in a system of unequal justice. These recommendations are based on proven models in other jurisdictions and seek to ensure that all people—regardless of their economic position—are treated fairly and equally.

Criminalization of the Poor

Nearly two centuries ago, the United States formally abolished the incarceration of people who failed to pay off debts. However, recent years have witnessed the rise of modern-day debtors’ prisons—the arrest and jailing of poor people for failure to pay legal debts they can never hope to afford, through criminal justice procedures that violate their most basic rights. Some people sit in jail while still presumed innocent—only because they don’t have the money to post bail.

An overwhelming majority of Nebraska jail inmates are deemed indigent. As we examined how court processes impact people who are poor, we found that the system often punishes defendants simply for not having money. Poor defendants in the criminal justice system are much more likely to experience incarceration because they lack the resources to pay fines or post bail, not because of the severity of their alleged crime.

This report looks at the monetary bookends of the criminal justice system: first, how bail is set when one is first arrested and second, what happens when one is found guilty and ordered to pay a fine and court fees.

Arrestees are presumed innocent and, for most offenses, may be allowed to go home to their family while they wait for their trial. They can do so if they post bail, which is set in the form of a cash amount. Immediately upon arrest, before a defendant is seen by a judge for an individual assessment, the bail amount is determined by a “schedule” that provides set bail amounts for particular offenses. These schedules vary widely from county to county. After the amount is set, a defendant may also go in front of a judge and request a lower amount. This report will first describe the current bail practices in Nebraska and how they impact the poor.

People who are found guilty of misdemeanors and traffic offenses are often not sentenced to do time—they are given a sentence of a fine, including court costs. Court costs can vary from $49 to $500. For example, if a defendant calls a witness they will ultimately be asked to pay the witness fee. In reality, many indigent people end up serving time behind bars simply because they cannot afford to pay those costs. This practice is known as “debtors’ prison,” and it is pervasive throughout the state. The report will also look at fines and fees collection and how it impacts the poor.

Both of these practices are economically inefficient since taxpayers pay thousands of dollars for defendants to sit in jail for days, weeks, and months. Debtors’ prison is a particularly illogical practice since the court costs and fines imposed ultimately do not generate income—rather, taxpayers pay for inmates to be incarcerated.

These practices don’t just impact the defendant and taxpayers—they ultimately affect the families and children of the defendant. Voices for Children Nebraska documented that one in ten children in Nebraska have a parent behind bars, and the effects of this experience often lead to economic and psychological instability for the child. Parents who cannot post bail or who are sitting out a fine in jail may lose their job, fail to meet a crucial bill deadline, and face eviction or loss of utilities. These all impact the entire family’s likelihood of financial stability and success.

These burdens fall on those who were already poor to start with, as those in the criminal justice system tend to be low income. “People convicted of felonies tend to be financially worse off before arrest and conviction than those not connected to the criminal justice system, and defendants tend to have higher unemployment rates than nondefendants…Nationally, the earned annual income of two-thirds of jail inmates was under $12,000 in the year prior to arrest.”

For this study, the ACLU examined court records from the four largest counties in Nebraska (Douglas, Lancaster, Sarpy and Hall) and personally observed county court arraignments and sentencings in the three largest counties (Douglas, Lancaster and Sarpy). In addition, we interviewed criminal defense attorneys across the state and other stakeholders. Through this research, we repeatedly found people sitting in jail simply for being poor and not being able to pay a couple hundred dollars in bail, fines or fees.

This practice is out of step with clear caselaw. The Department of Justice has begun to intervene in cases involving the criminal courts’ imposition of financial burdens on the poor and has stated, “incarcerating individuals solely because of their inability to pay for their release, whether through the payment of fines, fees, or a cash bond, violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” In March 2016, the Department of Justice issued guidance to all judges, calling for reform. The DOJ has enunciated several principles relevant to current Nebraska practices, including:

- Courts must not employ bail practices that cause indigent defendants to remain incarcerated solely because they cannot afford to pay for their release.

- Courts must not incarcerate a person for nonpayment of fines or fees without first conducting an ability to pay determination and establishing that the failure to pay was willful.

- Courts must provide meaningful notice and, in appropriate cases, counsel when enforcing fines and fees.

- Courts must not use arrest warrants or license suspensions as a means of coercing the payment of court debt when individuals have not been afforded constitutionally adequate procedural protections.

The report suggests ways Nebraska can come into compliance with the Department of Justice’s guidelines. The good news is that Nebraska doesn’t have as many problematic practices as many sister states. Some states have practices such as private bondsmen who use dangerous tactics to apprehend low-level offenders, high interest rates, late fees that make it nearly impossible to ever pay off court costs, and additional fees for serving jail time or applying for a public defender. While our system needs a significant overhaul, we are thankfully free of many of the shocking abuses documented in other states. Nebraska is well positioned to take immediate steps to protect the rights of people who are poor trapped in a cruel maze created by our criminal justice system.

Bail Reform

Bail refers to the amount of money a person has to pay to be released from jail after being arrested. Usually, a defendant pays ten percent of the total bail amount set by the judge. For instance, if $50,000 is set as bail, the defendant must pay $5,000 to go home.

Money bail should only be required when the prosecutor, after an individualized hearing, demonstrates the defendant’s release poses a significant danger or flight risk. As the Department of Justice has said, “Bail that is set without regard to defendants’ financial capacity can result in the incarceration of individuals not because they pose a threat to public safety or a flight risk, but rather because they cannot afford the assigned bail amount.” The presumption should always be in favor of release.

Over half of those in Lancaster, Sarpy, and Hall County jails on the days of our study had not been convicted of a crime.

Unfortunately, from our research it appears Nebraska courts aren’t routinely enforcing this presumption of release based on individualized factors. Instead, courts are treating all defendants the same based on the alleged crime rather than the defendant’s personal circumstances, or they are reflexively complying with requests for high bail amounts made by prosecutors.

The fallacy of our current bail system is that a mere dollar amount does nothing to ensure public safety or the guaranteed appearance of a defendant for trial. For example, a wealthy criminal defendant charged with a more serious crime may be able to post bail because he has financial resources. Meanwhile, a criminal defendant living in poverty who poses less risk must stay behind bars. Under this system, the only guaranteed outcome is the over-criminalization of people in poverty.

One’s wealth isn’t an indicator of how likely he or she is to appear in court for her court date. In fact, studies have shown that people released on their own recognizance without any money bail appear in court more often and defendants released on cash bail actually have higher failure to appear rates. It appears that Nebraska judges may currently impose bail not due to a fear of actual flight risk to another jurisdiction to avoid prosecution but simply due to a fear the accused may not show up for court dates. While a failure to appear imposes inconvenience and cost on the court system and witnesses, a failure to appear is not the same as fleeing.

Our current bond and fine systems criminalize poverty. Pretrial release programs which screen people for risk factors and can assess the level of supervision needed, are more effective at assuring someone appears in court than simply rewarding the person who can come up with a set amount of money. For one person, $100 is the same as $10,000 for another. One night in jail can mean the loss of a job, housing, and custody of children. If a bond requiring money is set, the primary factor considered by the court must be the person’s ability to pay. Our current system discriminates against the poor.

Joe Nigro, Lancaster County Public Defender

Many defendants do not show up for court because of unavoidable child care or work conflicts or because they were fearful and confused about the process. These issues can be resolved without using pretrial detention, and Nebraska has already had firsthand experience on how to ensure appearance in court. From 2009 to 2010, the Nebraska State Bar Association implemented a pretrial reminder pilot program in 13 counties and proved that a simple reminder postcard significantly lowered the number of people who failed to appear for court.

Some Nebraska counties currently offer a pretrial release that is contingent upon technological surveillance methods, including interlock devices on vehicles to test the driver’s alcohol usage and ankle monitors. Pretrial surveillance raises independent privacy and fairness concerns. Not only is it intrusive, it has often proven to be ineffective. For these reasons, most individuals who are pretrial should not be subjected to such monitoring. But for certain people, these devices could be among the least restrictive conditions necessary to ensure their return to court. Currently, however, all these devices come with a price tag that must be borne by the defendant, which only exacerbates the inequalities of the cash bail system. Officials in Lancaster County’s pretrial release program indicated they make every effort to provide no-cost technology options for defendants when the county is able to do so, though indigent defendants don’t have these options across the state. To the extent the state could devise a system that reliably determines the rare individuals who require pretrial monitoring, the fact that many rural counties have no such technology-based solutions raises concerns about disparate justice.

The Vera Institute reports that, nationally, 60% of jail inmates are pretrial, meaning either they have been denied bail or, more frequently, are unable to post bail. Out of our sample, we found that over half of inmates in Nebraska are pretrial defendants who are not convicted and presumed innocent. The ACLU believes that money bail should not be imposed unless the court concludes both that (1) the arrestee can afford the bail amount and (2) that less restrictive, nonmonetary conditions would be ineffective on their own. The presumption should always be in favor of releasing people with the least restrictive conditions needed, and money bail must be considered the most restrictive condition short of detention. An individual may only be held, with or without bail, if the court, after an individual assessment, has concluded by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant poses an imminent threat to public safety that no other condition or combination of conditions can reasonably protect against.

Being free on bail affects the ultimate outcome of the case. Several scholarly studies have found that comparable low-risk defendants who are detained for the entire pretrial period are up to five times more likely to receive a lengthier sentence than similar defendants who posted bail. Those held pretrial are also statistically more likely to be rearrested even if held only for a few days—our money bail system is actually promoting future criminal behavior.

Detention has devastating consequences beyond the disposition of the case. The psychological impact of being held in jail for even a few days can be severe. The World Health Organization has found that jail suicides often happen within the first few hours of incarceration due to the sudden isolation, the shock of imprisonment, and the individual’s uncertainty about their future. Nebraska is not immune from these tragedies—one database of recent jail deaths includes several entries for our state, most of which occurred while the defendant was in jail for four days or less.

Even those found innocent—or whose charges are dismissed—are punished by our current bail system. The bail money is returned to these people, but the court system still retains ten percent for court costs. In other words, a defendant whose family managed to put together a $50,000 bail will welcome him home when he is vindicated by a jury, but they will still lose $5,000 as a court cost.

Findings

To construct a snapshot of the pretrial jail population in Nebraska, on four random days in the summer of 2016 we acquired the jail lists of the four most populous counties: Douglas, Lancaster, Hall, and Sarpy. As more fully described in the Appendix, this meant we were able to capture individual inmates’ criminal charge, race, amount of time in jail, and bond amount.

When an inmate had more than one charge, we recorded and categorized that inmate by the most serious charge for which they were awaiting trial. If defendants were being held pretrial for more than one charge, we calculated the total amount of money they would need to post to be released that day.

When categorizing the severity of the charges, we divided crimes into the nine categories in the Appendix. See the Appendix for a full explanation of methodology.

Through court observations, and reviewing bail schedules and jail lists, we discovered many current practices in Nebraska do no comply with the law.

Many defendants are incarcerated for nonviolent crimes. An average of 17.5% of the pretrial defendants in the surveyed counties were in jail for nonviolent drug offenses. 11.4% were theft and shoplifting charges, and 7.3% were traffic related charges. In total, over half of the pretrial population were accused of nonviolent offenses. Notably, Hall County’s nonviolent pretrial population was the largest at 66.7%.

"First and foremost, we must ensure that we are in compliance with federal law when it comes to imposing fines and court costs on defendants. We should not be infringing upon people’s civil rights and incarcerating nonviolent offenders simply because they are poor and cannot afford to pay. We are in support of the ACLU’s efforts of reform."

Mary Ann Borgeson, Chair of the Douglas County Board of Commissioners

We also reviewed bail schedules, which are generally used for the initial period following an arrest; a defendant picked up after hours, on a weekend or on a holiday can still be released without seeing a judge if she has the cash listed on the bail schedule for her crime. These schedules are set by each of the 12 judicial districts, and the bail amounts vary widely based on geographic location. See the Appendix for bail schedules from each judicial district.

Examples of discrepancies from county to county include:

- DUI in the First Judicial District (Gage, Saline, Nemaha counties) will bail out at $3,500, while a DUI in the Third Judicial District (Lancaster County) needs only $2,500.

- Class I misdemeanors have bail at $10,000 in the Fifth Judicial District (Saunders, Seward, Platte, Hamilton counties) in comparison to $5,000 in the Fourth Judicial District (Douglas County).

- Driving on a suspended license requires $2,500 in the Third Judicial District (Lancaster County) but no bail need be posted in the Fifth Judicial District (Saunders, Seward, Platte, Hamilton counties) for the same charge.

- Domestic violence charges—even misdemeanors—automatically jump to $50,000 in the Second Judicial District (Douglas County) while other counties track the seriousness of the charge.

- Bail amounts automatically increase for non-residents in the First Judicial District (Gage, Saline, Nemaha counties) and Tenth Judicial District (Kearney, Adams counties).

- Officers have the discretion to release anyone without bail in the Second Judicial District (Sarpy County) except in cases of domestic violence and violations of protection orders. Residents may be released without bail in all cases if the arresting officer feels it is not necessary in the Tenth Judicial District (Kearney and Adams counties) and the Eleventh District (Dawson, Lincoln, Red Willow counties).

- Only a few bail schedules emphasize the expectation that requiring a bail is limited to circumstances involving public safety or flight risk: Seventh Judicial District (Madison County), Eighth Judicial District (Howard and Brown counties), Twelfth Judicial District (Scotts Bluff, Box Butte, Cheyenne counties).

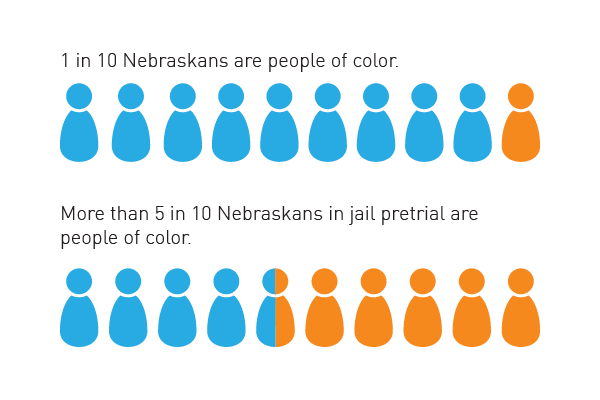

In addition, we found that people of color were disproportionately represented in the pretrial populations in comparison to the demographics of the county in which they were incarcerated.

In Lancaster County, whites compose 87% of the population, Blacks compose 4% and Hispanics compose 6%. In the Lancaster pretrial jail population, 59.1% are whites, 21.8% are Blacks and 8.2% are Hispanics.

In Hall County, the population is made up of 92% whites, 2% Blacks and 26% Hispanics. In the Hall pretrial jail population, 47.6% are whites, 20.6% are Blacks, and 25.4% are Hispanics.

In Douglas County, whites compose 81.1% of the population, 11.5% Blacks and 12.2% Hispanics. In the Douglas pretrial jail population, 39% are whites, 47% are Blacks and 10.7% are Hispanics.

In Sarpy County, the population is composed of 89% whites, 4% Black and 8% Hispanic. In the Sarpy pretrial jail population, 67.4% are whites, 16.3% are Blacks and 12.8% are Hispanics.

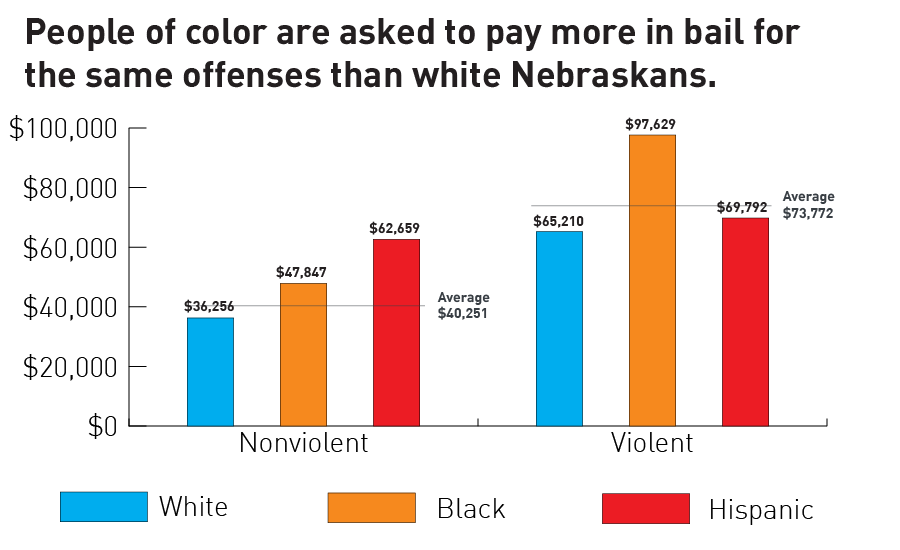

The racial disparities we discovered extend to the amount of bail as well. The average bond for a nonviolent offense was $40,251 on the days we studied and $73,772 for a violent offense. If you are Black, Hispanic or Native American, you can expect your bond to be $14,572 more than the average bond for a nonviolent offense and $13,109 more for a violent offense. This disproportionate treatment of people of color in the pretrial context shows how the court system systematically disadvantages people of color. Nebraska’s racial disparities are not an anomaly; studies across the U.S. have demonstrated that money bail specifically has a disproportionate impact on communities of color.

Interviews with criminal defense attorneys across the state suggest that the findings from the four surveyed counties are likely a fair representation of Nebraska’s pretrial system as a whole. Attorneys identified the final essential problem of high bail amounts: they can result in defendants pleading guilty simply to go home. “My clients regularly do the cost-benefit analysis,” reported one public defender. “They can’t post bail, and the trial date is a month away. The defendant knows if they plead guilty today to a misdemeanor, it’s ‘just’ a little charge on their record and they can go home. What they don’t factor in is what happens on the next charge they might have. The next judge sees this person has a criminal record and accordingly decides to nudge the bail amount up a little more, creating a vicious cycle. I’ve had clients with a viable defense who just threw in the towel so they could get back to their job, their children, and their lives.”

We were also struck in our court observations by how unrepresented defendants are treated while appearing before the judge and prosecutor. Without an attorney to advance arguments for a low bail, these defendants frequently did not even know how to articulate the request for release on their own recognizance or on a reasonable bail amount.

Increased incarceration leads to an increase in spending taxpayer dollars on people who are presumed innocent in the eyes of the state, many of whom are not a risk to society but are too poor to post bail. Our current bail practices hurt Nebraskans who are presumed innocent, have devastating impacts on their families, and are fiscally burdensome for counties. This is why the ACLU, along with professional associations and county officials around the country, are calling for immediate reform.

Examples of Reform

Pretrial defendants should not be incarcerated merely because they are poor and cannot gather enough money for bail. Not only is it unfair to the defendant, but it costs taxpayer money to have inmates sitting needlessly in jail. Many legal professional and criminal justice organizations have issued a call for the abolition of wealth-based bail similar to those used in Nebraska, including the American Bar Association, the National Association of Pretrial Services Agencies, the American Jail Association, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the American Probation and Parole Association, the Conference of Chief Justices, and the National Association of Counties.

There are reforms that court systems can adopt to effectively decrease the pretrial jail population and the number of indigent defendants incarcerated because they cannot post bail. Research shows that money is not an incentive for people to appear in court, and a growing number of systems have begun to adapt practices that allow the release of people who otherwise could not make even a small monetary bail.

Washington DC has a progressive pretrial release system that was implemented twenty years ago that allows 90% of their pretrial defendants to be released without paying money. It constructed a system that includes a twenty-four hour service where pretrial officers meet with the defendants and public defenders and conduct an individual interview to determine the chance of them committing a crime on release or failing to appear in court. This recommendation is given to the judge in court the next day, who usually follows it, in a process that takes less than five minutes.

Kentucky’s justice system has a 70% pretrial release rate. Only 4% of those arrested receive money bail. They use one statewide agency that assesses the risks of all defendants arrested so recommendations are consistent, yet individualized, and a majority of those arrested are released without paying bail.

Similarly, the federal system requires that “the judicial officer may not impose a financial condition that results in the pretrial detention of the person.” This law requires a more individualized assessment of factors that include employment, previous criminal record, the defendant’s character and the amount of evidence in the case. These factors are used to determine the public safety risk and the chance the defendant would return to court. The score results in one of three outcomes: no bail, bail, or release on conditions.

Reforming Nebraska’s Bail System

We propose the following reforms to aid Nebraska’s court systems in reconstructing their pretrial release processes so defendants are not incarcerated simply because they lack the financial resources to post bail.

Blue-ribbon commission of experts

Establish a blue-ribbon commission of judges, attorneys, legislators, probation officers, law enforcement and civil rights advocates to evaluate best practices in modern bail systems. The topics for the Commission’s study should include: the best risk assessment tool that takes into account local factors; the options of pretrial supervision and monitoring via technology such as GPS monitors or check-ins with pretrial case managers; the current practice of bail schedules; increasing public defender funding to ensure presence of defense counsel at initial appearance.

Localized actuarial risk assessment

The judicial branch should develop an actuarial risk assessment for defendants in custody awaiting their initial appearance in court that calculates one’s public safety risk while taking multiple factors into account which follow the best practices that have been tested in other jurisdictions. When such risk assessments are carefully created with local validation, with scrutiny to ensure no racial bias, with transparent data collection and scoring and which does not substitute for an individualized determination of release, they can ensure an expanded pretrial release program.

Citation in lieu of arrest

Police should use citation releases in lieu of arrest whenever possible, using best practice in-field tools to determine if a defendant needs to be taken into custody.

Appointment of counsel

Judges should ensure the appointment of counsel at hearings before imposition of bail.

Reminder systems

Clerks of the Court should adopt reminder systems by postcard, phone call, and/or text message to reduce the number of failures to appear.

Data collection

The judicial branch should collect and publish performance measures. Data showing the effectiveness of pretrial detention vs release will aid future policymakers.

Modern Day Debtors' Prisons

Fines and fees collection practices are another set of justice system procedures that punishes defendants for being poor. Defendants who are charged with a misdemeanor or infraction are usually sentenced to pay a fine within the statutory limits, plus at least $49 in court costs. The dollar amount defendants are ordered to pay can vary significantly. Judges are not required to impose these fines and costs—state law only provides that they “may” impose fines and fees as part of the sentence. Unfortunately, our survey suggests that few judges are exercising their discretion to waive or reduce fines and fees based on individualized assessments. As a result, it has become the norm to impose both fines and costs in nearly every case, and many people leave court with financial burdens that they cannot pay.

“…it shall be the duty of [the court] to discharge such a person from further imprisonment for such fine or cost…”

Neb. Rev. Stat. 29-2412

This practice of making people come to court to ask for an extension of time for payments presents additional obstacles for the poor and leads to the jailing of people for reasons that do not advance public safety. In practice, some people have difficulty getting transportation back to court or cannot easily get time away from work or child care obligations to come back to request an extension of their time to pay. Some people forget their deadline for paying. Some are not aware it is a possibility to show up to court to ask for more time.

Once a warrant is issued, there are significant negative consequences for the poor. Research has shown that people with an outstanding warrant will avoid visiting a hospital, attending school, or maintaining a job for fear of being picked up by police. If a defendant is arrested unexpectedly, the defendant has no opportunity to make arrangements for their children’s care and may result in the taxpayer incurring the additional burden of caring for children whose parent is behind bars. The arrest may cause the defendant to lose her job or miss paying a bill—eviction, joblessness, and further financial instability are the result. The experience of being in jail—even for just a few days—can have significant and far-reaching effects on the defendant’s physical and mental wellbeing that destabilize the individual and their entire family. These negative consequences have a disparate impact on people of color due to the racial wealth gap.

A modern-day debtors’ prison should not exist at all in Nebraska in light of our clear state law protections, long-standing United States Supreme Court case law, and recent federal guidance. Neb. Rev. Stat. 29-2412 provides that if a defendant is unable to pay a fine because of their financial circumstances, “…it shall be the duty of such court or judge, on his or her own motion or upon the motion of the person so confined, to discharge such a person from further imprisonment for such fine or cost, which discharge shall operate as a complete release of such fine or cost.” The court’s burden to determine whether a defendant can pay is clear: the judge should inquire into an ability to pay prior to imposing any financial penalty and no defendant should be incarcerated for nonpayment of fines and fees owed without another hearing in front of a judge. In our months of court watching, we did not witness even one judge inquiring into a defendant’s ability to pay prior to imposition of fines and fees.

Findings

We conducted 50 hours of county court watching in Douglas, Lancaster and Sarpy counties over the period of four months. We observed both arraignments and sentencing for misdemeanors under a total of ten different judges. We noted whether an attorney was present and whether the judge inquired into one’s ability to pay.

In addition to hours of in-person court observation, we looked at the same four counties’ jail lists and studied the court records of the sentenced inmates to identify any defendants serving time for unpaid fines.

Finally, we interviewed attorneys and indigent individuals from various counties about their experiences with facing a fine they couldn’t pay. For a complete description of our methodology, see the Appendix.

In court, we observed several concerning patterns:

- Out of months of observations where people were sentenced to fines and fees, we saw no inquiries from the judge asking if the defendant was able to pay the sentenced amount. We witnessed only one situation where court costs were waived.

- Out of months of observations, we only observed four people who had an attorney present during the imposition of a monetary fine and court costs.

- We found court records for many defendants were incarcerated for failing to pay fines and costs.

- In each county, we witnessed “pay or stay” sentences, where a defendant, without an attorney present, was told if she did not pay money that day she would be forced to sit out her fine in jail.

- Rights advisories were sometimes given in an abbreviated fashion that did not adequately warn the defendant of the consequences of pleading guilty. Notably, there was frequently no mention of immigration consequences. In at least one court, we saw a “group advisory” where the judge read off the advisory at the top of the hour and then never repeated it, despite the fact many defendants arrived later and never heard the advisory. We did not witness a single rights advisory that informed people that they could request a waiver of fines or fees upon a demonstration of inability to pay.

Community Service

In some counties, community service is offered as an alternative to sitting out a fine. Lancaster County has the most robust community service program, with options including evenings and weekends to permit a defendant to meet their court obligations with flexibility. Defendants in Lancaster County “earn” $10 per hour of community service towards their fine.

Community service can be problematic for many people. People with no ability to make financial payments are also often without reliable transportation or child care. People with disabilities find there are few options that they would be able to access. Rural defendants rarely have any community service option, according to our interviews of criminal defense attorneys in greater Nebraska. Even the Lancaster County program presents public policy concerns since the $10 per hour rate was not set by state statute or even regulation—it is simply the practice and has not been revised upward to account for inflation for over 13 years.

Community service can be an alternative for some people who are willing and capable of discharging their court fines, but the bottom line is clear: no one should be forced to sit in jail, perform labor, or otherwise be punished for not having the money to pay fines or fees.

Sentenced to Jail Without an Attorney

Nebraska law only requires the provision of a public defender if the defendant is facing jail time. We frequently observed judges rebuffing people’s inquiries about getting an attorney with statements such as, “The prosecutor isn’t seeking jail time and I’m not going to sentence you to any time, so you don’t qualify for a public defender.” As discussed above, many of these people ultimately do end up in jail when they can’t pay their costs—and yet they never had an attorney by their side. “I’ve sometimes run across a former client in jail or in court and asked them how they ended up there,” one public defender mentioned. “They tell me they couldn’t pay, and they weren’t allowed to call me because they were just swept up off the streets since they were considered to be in contempt of court. No one ever alerts the public defender when this happens; they started and ended without even a chance to discuss their options with counsel.”

Shockingly, most defendants were advised of the charge against them, pled guilty, and were sentenced to a fine without any inquiry into their ability to pay—and with no attorney present—in a single one-stop-shop process taking less than five minutes.

End Result: Modern Day Debtors’ Prisons

This system means that poor people are punished not for their offense but because of their poverty. This is arbitrary, unconstitutional, and financially ruinous for the individuals as well as the counties. It is fiscally imprudent for judges to impose fines and costs against indigent defendants. Instead of gaining money from the fine or court costs, taxpayers have to pay for defendants to be incarcerated. For example, Sarpy County finds itself considering the massive expense of a new jail, even though their own expert has pointed to one problem being the number of inmates who are serving debtors’ prison sentences. Beyond the jail costs, it is a drain on police resources when they are used in executing warrants for misdemeanor nonviolent offenders who simply are late in making a payment.

Nebraska has many successful models from sister states to look to as we end our debtors’ prison practices. For example, Ohio created a statewide bench card to walk judges through the appropriate inquiry to determine indigency before imposing court costs or fines. Michigan changed its court rules to ensure proper procedures to eliminate poor people sitting out a fine in jail. Colorado passed a state law banning the practice of jailing people who are too poor to pay a fine. Some of these reforms have been advanced by forward-thinking public policy makers, while some have come about after expensive protracted litigation. Nebraska should make immediate changes to its debtors’ prison practices to avoid change mandated by class action lawsuits.

Reforming Nebraska’s Fee System

We propose the following reforms to aid Nebraska’s court systems in reconstructing their fines and fees practices so defendants are not incarcerated simply because they lack the financial resources to pay.

Amend state law

The Legislature should amend Neb. Rev. Stat. 29-2412 to prohibit assessment of fines, fees or costs until the judge has held an individual hearing on ability to pay with appointed counsel present.

Consider ability to pay

Judges should change court processes so every defendant’s ability to pay is considered before imposition of fines, fees and costs. Consideration should include but not be limited to the defendant’s present employment, earning capacity and living expenses, dependents, outstanding debts and liabilities, public assistance, etc. Fines, fees and costs should not be imposed if the payment will subject the defendant or the defendant’s dependents to substantial financial hardship.

Bench card

The Nebraska Supreme Court should create guidelines for determining an inability to pay and policies for assessing fines, fees and costs. Courts in Ohio and Biloxi, Mississippi have created a model bench card to walk judges through the process of determining indigency that could be a model for future Nebraska practice.

Judicial training

The judicial branch should train all judges and other court personnel about federal and state laws that prohibit incarceration of defendants who are too poor to pay fines, fees, and costs as well as train all judges about their statutory authority to waive all non-mandatory fees when the defendant is indigent.

Appointment of counsel

Judges should ensure the appointment of counsel at hearings before imposition of fines, fees, and costs as well as when a person is reported for nonpayment.

Community service standards

The legislature should review the statutes relating to community service to ensure uniformity in its application across the state and ensure that community service is not imposed on defendants who lack transportation or the physical ability to participate in such work.

Court date reminders

The Clerks of the Court should institute proven, effective methods of reminding people of court dates via text message and/or postcard in order to reduce missed court dates.

Data collection

The judicial branch should collect and publish data regarding the assessment and collection of fines, fees, and costs, how collected funds are distributed, broken down by race and type of crime. Tracking should separately show imposition of fines, restitution, fees, and costs.

Conclusion

Nebraska’s state motto is “Equality before the law.” We need to work toward a system where all citizens are treated equally when they are charged with a crime or punished with a fine, regardless of their financial circumstances.

We look forward to further study of these issues, as this report did not reach a study of similar practices’ impact on people charged with more serious crimes, the use of debtors’ prison tactics in juvenile court, how the suspension of drivers’ licenses impacts defendants, and other aspects of our current system. As described in the Appendix, our survey was limited to only the most populous counties on randomly selected days; a comprehensive statewide survey is needed.

As one commentator noted, “it violates fundamental and longstanding principles of equality and fairness at the core of our legal system to keep a human being in a cage because of her poverty.”

Across the country, the ACLU has brought lawsuits to challenge court practices that burden the poor. Successful class action lawsuits are occurring across the country, often with the help of the U.S. Department of Justice as an interested party. In Jennings, Missouri, the city has reached a $4.7 million settlement to pay to people who were unjustly jailed for their inability to pay fines and court costs. Changing our state systems will require time and resources, but we can devote the effort to change voluntarily or await expensive litigation to force reform.

Our criminal justice system does not need to trap people who are poor in what amounts to modern-day debtors’ prisons.

With courts, prosecutors, criminal defense attorneys, policy makers and our community stakeholders working together, we can—and we must—work together to reform practices and reduce disparities to ensure justice for all.

Table of Offenses

|

CODE# |

Category |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Municipal violations |

City ordinance offenses such as trespassing, loitering, criminal mischief, terroristic threats, destruction of property, interfere with official duties, disturbing the peace, possession of alcohol, tampering with evidence or witness, disorderly conduct, lewd conduct, pandering |

|

2 |

Traffic |

Any traffic offense, including DUI, driving under suspension, no insurance |

|

3 |

Drug |

Drug related charges including distribution, manufacture, possession, and paraphernalia, drug tax stamp |

|

4 |

Theft/Fraud/Forgery |

Shoplifting, bad check, forgery, theft in any amount |

|

5 |

Burglary |

Any burglary charges |

|

6 |

Violation of supervision/status offense |

Violation of probation, violation of parole, fugitive, habitual criminal, failure to appear, escape, bench warrant |

|

7 |

Weapon |

Weapon offense excluding use of a weapon against a person – that would be captured by “violent” category: includes possession of weapon or ammunition by a felon, possession of illegal weapon |

|

8 |

Sex offenses |

Sexual assault, sex offender failure to register, possession of child pornography |

|

9 |

Violent |

Violent offense include murder, manslaughter, robbery, kidnap, carjacking, use of weapon, aggravated assault, arson, assault, stalking, violation of protection order, domestic violence, child abuse, motor vehicle homicide |

Methodology

Bail Study

To study bail practices, we requested data from four counties on randomized dates: Lancaster County on June 9, Hall County on June 29, Sarpy County on July 1 and Douglas County on September 12. We used open records requests to obtain the list of people currently housed in each jail, eliminated all people serving a sentence and all people being held on an ICE or extradition hold, and categorized all remaining pretrial individuals. Approximately one-half of every county was pretrial. Other holds such as ICE or extradition holds were less than 2% of the jail populations.

There were some pretrial detainees whose bond amount or charge was not available in court records. They may have been on a hold for extradition or ICE, or the data may have just been missing. We eliminated those detainees from our survey. 1.2% of the sample size was missing data and therefore not included in the final data in this report.

Other than the exceptions described above, we were able to research every single pretrial detainee in Hall, Sarpy, and Douglas for our sample days. We used a random sample of one-half of the pretrial detainees in Lancaster County. On the randomized dates, the pretrial populations studied were as follows: 840 in Douglas, 141 in Sarpy, 63 in Hall and 110 in Lancaster, for a total of 1,154 pretrial detainees.

We then used Nebraska’s online court records system JUSTICE to examine the pretrial individuals’ court record. We recorded all pending charges, the person’s race, the booking date and the bond amount.

There was one anomaly in our gathering of race data: Sarpy County’s jail list did not include any Hispanic inmates. They apparently classify all Hispanics as white. We consulted with the Nebraska Latino American Commission and then decided to proceed by categorizing Hispanic inmates by surname and their perceived race in the booking photo. While this posed a level of discomfort, we did not wish to omit the Hispanic representation from Sarpy County.

As shown in the Appendix, we grouped crimes into nine categories that clustered similar offenses together. We ranked those offenses from the least serious municipal violations such as loitering and trespass to the most serious offenses involving violence such as assault, child abuse, and murder. This permitted us to then rank the seriousness of the charges pending against the pretrial population. Throughout the report and in the graphs, “nonviolent” meant offenses from the first six categories and “violent” means any offense involving a weapon, a sex offense, or a violent offense.

Many individuals had multiple charges. For example, an individual pulled over for speeding might be found to be intoxicated and during her arrest, she might have punched the arresting officer. This hypothetical driver started with a low-level Category 2 traffic offense (speeding and DUI) but her assault of the officer means she would be rated the highest Category 9 violent offense in our final label for her case.

Some individuals had two open court cases—in other words, not just multiple charges in one court filing but several separate docketed cases. For example, a shoplifter who managed to post his initial bail might have gotten out, been re-arrested for driving on a suspended license, and now be sitting in jail on two separate cases with two separate bail amounts. For those individuals, we calculated the total amount that they would need to post to go home that day to arrive at their current bail amount.

In addition to calculating bail amounts through the aforementioned process, we conducted interviews with criminal defense attorneys. We interviewed private attorneys whose clients hired them in a criminal defense case, public defenders, and attorneys who were appointed by the court to provide indigent defense. We interviewed 21 attorneys whose practices stretched from Scottsbluff to Falls City.

Debtors’ Prison Study

Between June and September 2016, law students and undergraduate pre-law students watched approximately 50 hours of court proceedings in Douglas, Lancaster, and Sarpy counties. Due to the distance from our office, we did not conduct any court observation in Hall County. Our observations were of ten different county court judges who were currently presiding over arraignments and sentences—the judges were not selected for observation, but rather were simply whoever was assigned to the courtroom on the days of observations.

The court observations were conducted after each observer was trained by two attorneys and taken to court with an attorney to train in person. A matrix was provided for the observers that captured name, charge (if available), whether an attorney was present with the defendant, whether the judge provided a rights advisory, whether the rights advisory included a specific warning about immigration consequences, whether the judge made any inquiry into the defendant’s ability to pay before imposing court costs or fines, and the sentence.

In addition to the in-person court observation, we also used court records from the same random sample days from the four counties in our bail reform. We separated the jail populations into “pretrial” and “sentenced” for the bail study. For the purposes of the debtors’ prison study, we then used the JUSTICE database to examine the charge for those serving a sentence.

Identifying those sitting out a fine for inability to pay was difficult due to differences in each county’s practices. For example, some defendants who missed the deadline to pay court costs and fines were listed as serving a sentence for “Failure to appear,” or “Failure to pay,” while others were simply listed with the underlying charge and no indication this was sitting out a fine. We used JUSTICE to review court records for all defendants listed as “Failure to appear” and “Failure to pay” to determine whether it was a debtors’ prison incident.

Interviews were conducted to supplement the data we collected through court proceedings. We interviewed approximately 20 individuals who we observed in court by contacting them after their arraignment and/or sentencing to learn more about individual cases. We also asked about debtors’ prison practices while interviewing the criminal defense attorneys we interviewed for bail reform. Finally, we interviewed approximately 10 civil practice attorneys who primarily handle bankruptcies and work with people in financial crisis to inquire about their clients’ experiences with court-ordered fees and costs. The personal stories shared throughout the report were from people we met during the observation sessions or whose attorneys referred their client to the ACLU.

Bond Schedules

Bond schedules can be found on pages 43-71 of the PDF of the full report.

Related content

ACLU Files Court Challenge to State of Nebraska’s Execution Protocol

March 26, 2018Nebraska Is Illegally Obtaining and Storing Execution Drugs in...

March 12, 2018ACLU Statement on Dept. of Corrections Issuing of a Death Notice

January 19, 2018ACLU Applauds Introduction of Bill Limiting Solitary Confinement...

January 5, 2018

I spent my 16th Birthday Alone in a Cell

January 5, 2018ACLU of Nebraska Applauds Introduction of Bill Addressing High...

January 3, 2018

Thanks to you - 2017 Victory List

December 22, 2017